La Corte Suprema de Iowa escuchó los argumentos en el caso de Woodbury County

/Los jueces de la Corte Suprema de Iowa. En la fila de enfrente, de izquierda a derecha: Brent Appel, Susan Christensen y Thomas Waterman. Fila trasera, de izquierda a derecha: Dana Oxley, Edward Mansfield, Christtopher McDonald y Mattew McDermott.

Ashley Martínez Torres

Especial para LA PRENSA Iowa

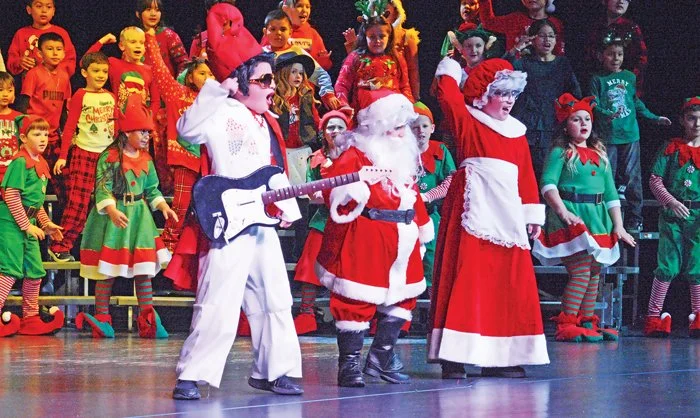

La comunidad de Denison tuvo la oportunidad de ver en acción el trabajo de la Corte Suprema de Iowa dentro del auditorio Donna Reed el pasado 25 de octubre.

Un grupo de jueces conformados por Susan Larson Christensen (Harlan), Thomas Waterman (Davenport), Edward M. Mansfield (Polk County), Christopher McDonald (West Des Moines), Dana Oxley (Swisher), Matthew McDermott (West Des Moines) y David May (Polk City) escucharon los argumentos orales de apelación de los abogados en el caso del Estado de Iowa vs Fethe Feshaye Baraki del condado Woodbury.

Cabe mencionar que el proceso de apelación es distinto al de un juicio; cuando un juicio termina, si alguna parte no está satisfecha con el resultado que recibió en un juicio, esta puede apelar la decisión a una corte superior, mejor conocida como corte de apelación, donde un grupo de jueces están a cargo de la decisión final – a comparación de un juicio, donde solo un juez está presente.

Durante la sesión, se cuestionó si la corte del distrito del condado de Woodbury se equivocó al aprobar la moción de suprimir el uso de los resultados de una prueba de alcoholímetro ya que el inglés del acusado es extremadamente limitado, y no comprendía el aviso de consentimiento implícito, el cual debe de ser leído a una persona sospechosa de operar un vehículo bajo la influencia de intoxicación.

El estado presentó la apelación ante la corte, por medio del abogado Zachary Miller, que estuvo a cargo de dar el argumento de apertura. El argumento que la corte de distrito debía de basar la decisión del caso, estaba basado en que si el oficial de policía hizo todo lo posible para asegurarse de que el acusado había entendido sus derechos al momento de la detención.

En mayo del 2021, un oficial detuvo a Fethe Feshaye Baraki en Sioux City bajo sospecha de que estaba intoxicado, pero rápidamente se dio cuenta de que existía una barrera de lenguaje significante entre ambos – Fethe era originario de Eritrea, un país en el norte de África, y hablaba poco inglés.

El oficial buscó la manera de comunicarse con el acusado por medio de Language Line, un servicio telefónico de interpretación, de igual manera trató de usar el servicio de traductor de Google, pero ninguno de estos medios contaba con la capacidad de traducir del inglés al Tigriña, el lenguaje natal de Fethe.

Cabe aclarar que, bajo la ley de Iowa, un motorista se considera que ha dado su consentimiento para tomar una prueba que determinara el nivel de alcohol o drogas en su sistema si un oficial de policía tiene sospechas razonables de que la persona estaba manejando intoxicado. Aun así, el oficial a cargo está obligado a informarle al motorista sobre ciertos derechos y consecuencias de aceptar o negar la prueba, como por ejemplo la revocación de la licencia de conducir por un año.

Con el simple hecho de mencionar que el oficial en turno no tenía más opción que llevar a cabo el examen de toxicología a Fethe, los jueces Mansfield y Christensen rápidamente interrumpieron al abogado.

“Usted dijo que el oficial no tenía otra opción. ¿Podría [el oficial]haber obtenido una orden de registro?,” preguntó Juez Mansfield. A lo que la Juez Christensen agregó que el oficial tenía hasta dos horas para pedir dicha orden, y que el incidente entre el acusado y el oficial duro alrededor de 45 minutos.

A esto el abogado aceptó que si el oficial hubiera esperado otra hora el estado tendría un caso más firme, pero que a la vez no había manera de saber si se podría conseguir un intérprete pronto. Él también explicó las formas en las que el oficial trató de comunicarse de forma clara con el acusado, incluyendo la oportunidad de llamarle a un conocido que pudiera interpretar para el acusado.

Otras preguntas por parte del jurado incluyeron: ¿Cuál es el propósito del aviso de consentimiento implícito? ¿De qué servía usar el inglés con el acusado si este no estaba seguro de lo que se estaba diciendo?

Por su parte la abogada defensora Vidhya K. basó su argumento en el precedente, una decisión de un caso anterior, del caso del Estado vs García (2008) – un caso similar al de Fethe, donde el acusado hablaba poco inglés y recibió un examen de toxicología que demostró que estaba bajo los efectos del alcohol, pero con la diferencia que en el caso García, el oficial de policía no mostró el esfuerzo suficiente para asegurarse de ofrecer la información en el lenguaje del acusado.

Vidhya explicó que, debido al inglés limitado de su cliente, el examen de toxicología no debería ser tomado en cuenta ya que Fethe no había comprendido las consecuencias de lo que esto implicaba, y por ende no tuvo la oportunidad de negarse; ella también argumentó que el policía en turno no tomó todas las medidas necesarias para que el acusado comprendiera lo que estaba pasando.

Sin embargo, los jueces tenían otra opinión.

“Este es un caso que ha estado pendiente por meses y la pregunta sigue surgiendo: ¿Qué más pudo hacer el oficial? Es una pregunta simple y hasta el momento usted [la abogada] ha respondido que no está segura,” comentó el Juez McDonald. “Entonces, si usted no tiene una respuesta, ¿Cómo podemos esperar a que [el oficial] supiera que hacer?"

Otras preguntas incluyeron: Su cliente salió del auto cuando se le pidió, ¿esto no demuestra que el tiene cierto entendimiento del lenguaje? ¿En cuántos lenguajes debería el personal de policía tener la información disponible en caso de una situación así? ¿es culpa del policía el que no hubiera interpretes disponibles? ¿Está buscando un pase para este caso en específico?

Como se menciona previamente, un caso de apelación es distinto a un juicio; en este caso, ambas partes tuvieron 15 minutos para presentar sus argumentos, pero el abogado representando al estado tuvo la última palabra debido a que el estado estuvo a cargo de pedir la apelación.

Usualmente, al termino de los argumentos orales, los jueces de la Corte Suprema se reúnen en privado para tomar una decisión, pero esta vez decidieron dar paso al público para que hicieran preguntas relacionadas a la corte y los juicios en general, mas no sobre el caso que los presentes habían presenciado. Es por esto que el jurado se reunirá en otra ocasión para llegar una conclusión.

Este artículo es patrocinado por Western Iowa Journalism Foundation.

Translation

Iowa Supreme Court hears oral arguments for Woodbury County case

The Justices of the Iowa Supreme Court. In the front row, from left: Brent Appel, Susan Christensen, and Thomas Waterman. Back row, left to right: Dana Oxley, Edward Mansfield, Christtopher McDonald, and Mattew McDermott.

Ashley Martínez Torres

Especial para LA PRENSA Iowa

The community of Denison had the opportunity to see the Iowa Supreme Court's work in action inside the Donna Reed Auditorium on October 25th as well as the opportunity to learn more about the Iowa court system.

A panel of judges consisting of Chief Justice Susan Larson Christensen (Harlan), Justice Thomas Waterman (Davenport), Justice Edward M. Mansfield (Polk County), Justice Christopher McDonald (West Des Moines), Justice Dana Oxley (Swisher), Justice Matthew McDermott (West Des Moines) and Justice David May (Polk City) heard oral arguments from attorneys in the case of State of Iowa v. Fethe Feshaye Baraki of Woodbury County.

The appeal process is different from that of a trial; When a trial ends, if any party is not satisfied with the outcome they received in a trial, they can appeal the decision to a higher court, better known as an appellate court, where a group of judges are in charge of the final decision – as opposed to a trial, where only one judge is present.

During the appeal trial, it was questioned whether the district court in Woodbury County erred in approving the motion to suppress the use of breathalyzer test results because the defendant spoke English in a limited manner and did not understand the implied consent notice, which must be read to a person suspected of operating a vehicle while intoxicated.

Since the state filed the appeal, attorney Zachary Miller, representative for the state, was in charge of giving the opening argument; He argued that the District Court should have based its decision on whether the police officer did everything possible to make sure the defendant understood his rights.

In May 2021, an officer stopped Baraki in Sioux City on suspicion that he was intoxicated, but quickly realized that there was a significant language barrier between the two – Baraki was originally from Eritrea, a country in North Africa, and spoke little English.

The officer looked for a way to communicate with him by calling Language Line, a telephone interpretation service, and using Google Translate, but neither of these means had the ability to translate from English to Tigrinya, the defendant´s native language.

Under Iowa law, a motorist is deemed to have consented to take a test that will determine the level of alcohol or drugs in their system if a police officer has reasonable suspicion that the person was driving while intoxicated. Even so, the officer in charge is obliged to inform the motorist about certain rights and consequences of accepting or denying the test, such as the revocation of the driver's license for one year.

While District Court Judge Roger Sailer, who served as presenter in this case, warned those present that the case would be a quick process and judges could interrupt lawyers at any time, no one was prepared for the constant pressure lawyers faced.

By simply mentioning that the officer on duty had no choice but to conduct the chemical breath test on Baraki, Judges Mansfield and Christensen quickly interrupted the attorney.

“You said that the officer had no other option. Could he have obtained a search warrant?” asked Justice Mansfield.

To which Judge Christensen added that the officer had up to two hours to request the warrant, and that the incident between the defendant and the officer lasted about 45 minutes.

To this, the lawyer agreed that if the officer had waited another hour the state would have a stronger case, but that at the same time there was no way to know if an interpreter could be available at all. He also explained the ways in which the officer tried to communicate clearly with the defendant, including the opportunity to call a friend who could interpret for the defendant.

Other questions from the jury included: What is the purpose of the implied consent notice? What was the use of using English with the defendant if he was not sure what was being said?

Miller’s time came to an end, and it was time for defense attorney Vidhya K. Reddy to share her argument; she based her argument on precedent, a decision from a previous case, from State v. Garcia (2008) – a case similar to Baraki’s, where the defendant spoke little English and received a chemical breath test that showed he was under the influence of alcohol, but with the difference that in Garcia the police officer did not show enough effort to make sure the defendant understood what he was asked to do.

Reddy explained that, due to his client's limited English, the test should not be considered as evidence since Baraki did not understand the consequences of what this implied and therefore did not have the opportunity to refuse; She also argued that the officer on duty did not take all necessary steps to make the defendant understand what was going on.

However, the judges had a different opinion.

“This case has been pending for months, and it's very simple: what else should this officer have done? I think your answer is you don't know,” Justice McDonald said. “Well, how is [the officer] supposed to?”

Other questions included: Your client got out of the car when asked, doesn't this show that he has some understanding of the language? In how many languages should police staff have the information available for this type of situation? Is it the officer’s fault that there were no interpreters available? Are you looking for a pass for this specific case?

As mentioned above, an appeal case is different from a trial; In this case, both sides had 15 minutes to present their arguments, but Miller had the final say because the state was in charge of requesting the appeal.

Usually at the end of oral arguments, the Supreme Court justices meet privately to make a decision, but this time they decided to give the public the chance to ask questions related to the court and trials in general, but not about the case that those present had witnessed. This is why the jury will meet on another occasion to reach a conclusion.

This article is sponsored by the Western Iowa Journalism Foundation.